#HTE

Taylor Host has been operating his artificial intelligence startup out of Hong Kong for more than two years. The American entrepreneur has clients from Europe, North America and Asia, but he settled in the city for its adjacency to Southeast Asia and mainland China’s massive market.

Miro, which Host co-founded in 2017 with a British software engineer, had bootstrapped to six employees before raising a small note investment. Backed by Silicon Valley-based SOSV, it’s now seeking $2 million in a new funding round. As trade tensions between China and the U.S. drag on, the company is considering relocating for the first time because being a Hong Kong entity starts to turn off western investors.

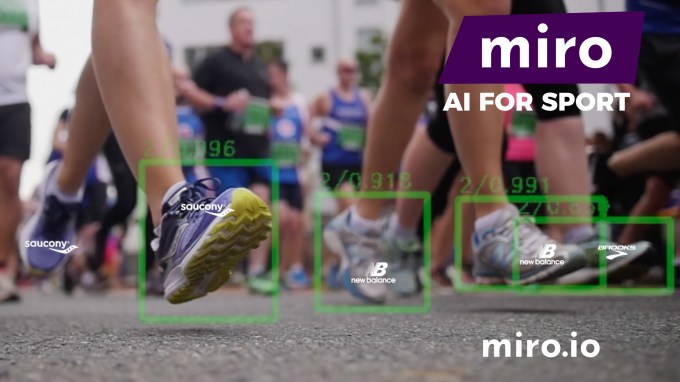

Miro uses computer vision to tag images and videos of runners for the brands they wear. It then attributes that data — sporting goods purchases — to consumers profiles that are part of its clients’ customer relations management (CRM) system. Miro’s AI processes data in markets around the world, but China data, in particular, is desirable for western sports brands.

The Chinese rising middle-class has been fueling a marathon fever in recent years as they search for a healthier lifestyle. When they participate in a race, Miro’s sensors could be tracking their shoes and outfits for event organizers and sponsors. The technology has so far been used in nearly 500 events around the world and analyzed more than 10 million athletes — while most of the technical development has been conducted in Hong Kong.

“My co-founder and I both spent a considerable amount of time in Hong Kong. The majority of our team would call themselves Hong Kong Chinese, so we have a very strong foothold in Hong Kong and we love it here,” Host told TechCrunch over a phone interview.

“Lately though, it’s become very difficult to rationalize keeping the business in Hong Kong. There’s a number of reasons for that, but I think the ones that stand out are geopolitical.”

For one, Host has sensed a “dramatic” sentiment change among western investors towards Hong Kong, where a contentious extradition bill triggered a wave of mass protests recently. At the heart of the issue are fears that the special administrative region is ceding autonomy to Beijing. Critics cite examples of the disappearance of a Hong Kong bookseller and a Financial Times journalist’s visa denied by the local government.

Miro, a Hong Kong-based startup, uses computer vision to tag images and videos of runners for the brands they wear. / Photo: Miro

In an alarming move, the U.S. government stated the extradition bill “imperils the strong U.S.-Hong Kong relationship” that includes a special trade arrangement independent from that of mainland China.

Hong Kong’s leader Carrie Lam announced in early July that the bill was “dead“, but the die has been cast as concerns linger for Hong Kong’s autonomous status. Businesses in the territory now risk being dragged into the U.S.-China trade war.

In March, Miro won a pitch competition at SXSW and has since attracted institutional investors of all sizes. But two of its potential backers based in the U.S. have decided to leave the negotiation table seeing Hong Kong as a risk.

“Not a single firm has overlooked the issue of us being a Hong Kong-based company,” said Host. “There is zero appetite from the U.S. investors who we have talked to to invest in our Hong Kong entity right now.”

The risk of backing Miro, which processes seas of data with image recognition capabilities, is more pronounced than funding companies with little or no core technology as intellectual property is one of the main targets of the U.S.-China negotiations.

“Foreign venture capitalists have become more vigilant about investing in Chinese AI and chips companies, even when they don’t own core technology,” Joe Chan, founding partner of Hong Kong-based MindWorks Ventures, told TechCrunch in an interview.

Meanwhile, the trade war has had a tangential impact on U.S. fundings for Chinese startups that focus on education, lifestyle and other non-deep tech sectors, according to a handful of investors who we have spoken to in recent months.

Southeast Asia gains

With the help of legal and tax consultants, Miro has recently shifted to a U.S. entity by registering in Delaware but will keep its operations in Hong Kong. It’s a move which, in Host’s words, has “pleased and allowed the company to move forward” with some of its interested U.S. investors.

“It was a requirement of our conversations with those U.S. investors that they are investing in a U.S. — not Hong Kong — entity,” the founder noted. “If you are dead set on your company being the biggest company in your industry, why would you even consider being in a place that has so much uncertainty and risk?”

For China-based companies whose cross-border business is anchored in Asia, Southeast Asia could be a safe haven from the trade war. As Chan observed, some Chinese startups have intended to move to Singapore “to become less politically sensitive.”

Miro won a pitch competition at SXSW and has since attracted institutional investors of all sizes. But potential backers have decided to leave the negotiation table seeing Hong Kong as a risk. / Photo: Miro

Miro is also hedging risks by looking to Southeast Asia, which many would argue is emerging as a winner from the U.S.-China fight. Like China, the region has a burgeoning middle class that is getting into running and a range of other hobbies and habits that will spawn startup ideas.

Indeed, there’s been a lot of chatter about the rise of the region with a population of 640 million. A few big-name global investors, including Warburg Pincus and TPG Capital, have set aside new funds over the past few months to back Southeast Asian startups. Corporate investors including Tencent, Alibaba, Didi Chuxing and JD.com, are also clamoring to gain a foothold in this rising part of the continent, as we wrote two years ago.

“On a macro level, the trade war certainly has a substantial impact on China’s economy, so we are seeing a lot more money flowing to Southeast Asia,” said Chan.

“For example, some manufacturers have moved to Indonesia where labor is cheaper. China’s tech industry — and this is not entirely linked to the trade war — is reaching saturation and dominated by the BAT [Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent], so the window of opportunity is small. Meanwhile, Southeast Asia is still in development.”

In a way, the trade war has accelerated the shift of attention from China to neighboring countries. The momentum was what brought Miro to visit one of the region’s largest tech conferences Techsauce recently.

“Nobody is talking about the trade war out here in Bangkok. We are talking about how Southeast Asia is exploding. And that is not just Chinese investors. It’s western investors too,” said Host.

https://techcrunch.com/2019/07/17/us-china-trade-war-hong-kong/