asia

#HTE

The fate of TikTok in the United States got even more confusing this week. The U.S. Justice and Commerce Departments sent conflicting messages today about TikTok’s future, which is now up in the air with the upcoming administration transition.

The Department of Commerce said Thursday it would abide by an injunction issued October 30 by the District Court in the Eastern District of Pennsylvania that would have blocked TikTok from operating in the U.S. starting from today. In a statement, the department said it is complying with the court’s order and its prohibition against TikTok “HAS BEEN ENJOINED, and WILL NOT GO INTO EFFECT, pending further legal developments.”

But on the same day, the Justice Department appealed the Pennsylvania court’s ruling just as it was set to go into effect.

But wait! It gets even more convoluted: another court–the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington–just set new deadlines in December for ByteDance, TikTok’s Beijing-based parent company, and the Trump administration, to file documents in a case involving a divestment order that would force ByteDance to sell TikTok to continue operating in the U.S.

ByteDance reached an agreement with Oracle and Walmart in September, but the future of the deal is also uncertain.

The Justice Department’s appeal is part of a lawsuit filed against the U.S. government on September 18 by three TikTok creators, Douglas Marland, Cosette Rinab and Alec Chambers. Each has more than a million followers on TikTok, which has about 100 million users in the U.S., and argues that a ban would impact their ability to earn a living from brand collaborations on the app.

On Oct. 30, Judge Wendy Beetlestone issued an injunction against the U.S. government’s restrictions. In her ruling, Beetlestone wrote that the “government’s own descriptions of the national security threat posted by the TikTok app are phrased in the hypothetical.”

This case is separate from the one ByteDance filed against the U.S. government in a federal appeals court in Washington D.C. Earlier this week, ByteDance asked that court to vacate the U.S. order forcing it to sell the app’s American operations. ByteDance told TechCrunch in a statement that without an extension on the November 12 deadline, it “[had] no choice but to file a petition in court to defend our rights and those of our more than 1,500 employees in the U.S.”

The Commerce Department’s statement today, along with the Justice Department’s appeal and the new deadlines in the divestment case, underscore the confusion about the future of the Trump administration’s actions against TikTok after President-Elect Joe Biden takes office on January 20.

While some analysts believe the Biden administration may give Chinese tech companies that were targeted under the current administration, including Huawei and ByteDance, a chance to re-negotiate with the government, that may take second priority as Biden deals with domestic issues, including the resurgence of COVID-19 in the U.S.

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/12/the-u-s-government-sends-mixed-messages-about-tiktoks-future/

#HTE

A Y Combinator-backed startup that is helping major companies efficiently listen to how happy — or unhappy — their employees are and resolve their issues on time to retain talent just raised a new financing round from several high-profile executives.

InFeedo, a four-year-old people analytics SaaS startup with headquarters in Gurgaon, said on Thursday it has raised $3.2 million in its Series A funding round. Bling Capital led the round and its founder, Benjamin Ling, who previously served as a general partner at Khosla Ventures and executive roles at Google and Facebook, has assumed a board seat at InFeedo.

Simon Yoo of Green Visor Capital, Maninder Gulati, chief strategy officer at budget lodging startup Oyo, Munish Varma, managing director for EMEA region at SoftBank and Girish Mathrubootham, founder of SaaS giant Freshworks, are among those who participated in the round.

As a business grows up and the headcount balloons over thousand, ten thousand, and tens of thousands, it becomes impossible for the chief executive to engage meaningfully with employees to gauge their morale and understand if there is anything they wish the company changed.

InFeedo is tackling this challenge through Amber, a chatbot it has built that touches base with employees periodically to quickly check how things are going, explained Tanmaya Jain, founder and chief executive of the four-year-old startup.

On the backend, executives can check the status of their employees across the company and how likely some individuals — especially the top talent — are at leaving the firm. They can check exactly what issues these employees have raised in the past, and whether their concerns were resolved.

Amber is able to track the progress because it remembers what an employee has previously shared. So each future conversation begins with it asking whether anything has meaningfully changed since the last time it spoke to the employee.

“Almost three years ago, we started using Amber at OYO and I was amazed by the product. We were using this for executive decision-making, to get an accurate pulse of our employees across geographies, functions as we were expanding across the world. I actually reached out to Tanmaya and am excited to be part of this journey,” said Oyo’s Gulati in a statement.

InFeedo has amassed more than 100 customers — including GE Healthcare, Puma, steel-to-salt conglomerate Tata Group, telecom firm Airtel, computer vendor Lenovo, Oyo, Indian internet conglomerate Times Internet and edtech giant Byju’s — across over 50 countries. More than 300,000 users today use InFeedo’s service. The startup today is clocking an annual revenue run rate of $1.6 million, something Jain said he is working to get to $10 million.

For Jain, 26, InFeedo’s current avatar is the third pivot he has made at the startup. InFeedo started as an edtech platform to create a feedback loop between students and their teachers. The startup then explored building a social network for companies. Neither of those ideas gained much traction, he explained. During the third attempt, Jain said he spent days at his early customers to understand exactly what features they needed.

As part of the new financing round, InFeedo, which has raised $4 million to date, said it has delivered partial exits of $1.1 million to early investors and early employees or those who left. “Helping people around me make so much money has been one of the most fulfilling things for me,” he said, adding that this liquidity at the time of a pandemic has been immensely useful to many.

The startup plans to deploy the new funding to make Amber understand multiple languages, a key aspect that Jain said would help the startup better serve clients in adjacent markets to India. InFeedo also wants to expand the use cases of Amber and experiment with new technologies such as GPT-3. It is also hiring for product, engineering and marketing leadership roles.

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/12/infeedo-raises-3-2m-led-by-bling-capital-delivers-1-1m-exit-to-early-employees-and-investors/

#HTE

PUBG Mobile will make its return to India in a new avatar, parent company PUBG Corporation said on Thursday. TechCrunch reported last week that the South Korean gaming firm was plotting its return to the world’s second largest internet market two months after its marquee title was banned by the country.

Additionally, the company said it plans to make investments worth $100 million in India, one of the largest markets of PUBG Mobile, to cultivate the local video game, esports, entertainment, and IT industries ecosystems.

More to follow…

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/12/pubg-mobile-announces-return-to-india-new-game-100-million-investment/

#HTE

China’s e-commerce behemoths Alibaba and JD.com again claimed to have set records during the world’s largest shopping event, Singles’ Day. The figures can often be gamed to paint a rosy picture of perpetual growth, journalists and analysts have long observed, so they are limited metrics for measuring the firms’ performance or Chinese consumers’ purchasing power in times of COVID-19.

Nonetheless, the heavy workload for express couriers is indisputably real and visible.

Starting the second week of November, I noticed parcels beginning to pile up outside my apartment compound in downtown Shenzhen, awaiting their final doorstep delivery. Courier workers dashed in and out of elevators, hurling boxes of items that shoppers bought at discounts or after being tricked by elaborate sales formula into thinking they got good deals.

Singles’ Day will see 2.97 billion packages delivered across China between November 11-16, the period when merchants begin shipping after a pre-sale period, according to a notice from the State Post Bureau. That marks a 28% increase from the year before and doubles the normal daily volume.

It also means that, on average, every person in China is set to get more than two parcels during the shopping spree. They will also receive plenty of e-commerce waste, from cardboard, tape, to wrapping bubble. Both JD.com and Alibaba’s Cainiao logistics arm have rolled out programs aiming to make online shopping more sustainable.

While coronavirus infections continue to climb in many countries, China has had few local transmissions for months. As such the pandemic has had a limited impact on delivery speed during Singles’ Day this year, both JD.com and Alibaba told TechCrunch.

Still, the companies have deployed new rules to ensure safety and speed. JD.com, for instance, claimed that it sanitizes its delivery stations and trucks and requires workers to wear masks and take the temperature on a daily basis, practices that are now standard in the country’s logistics sector. Pre-sale also allowed it to allocate inventory closer to consumers in advance. It said that 93% of the shipment orders fulfilled by its own logistics system was completed under 24 hours.

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/11/china-3-billion-parcels-post-covid-singles-day/

#HTE

In a new filing, TikTok’s parent company ByteDance asked the federal appeals court to vacate the United States government order forcing it to sell the app’s American operations.

President Donald Trump issued an order in August requiring ByteDance to sell TikTok’s U.S. business by November 12, unless it was granted a 30-day extension by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS). In today’s filing (embedded below) with the federal appeals court in Washington, D.C., ByteDance said it asked the CFIUS for an extension on November 6, but the order hasn’t been granted yet.

It added it remains committed to “reaching a negotiated mitigation solution with CFIUS satisfying its national security concerns” and will only file a motion to stay enforcement of the divestment order “if discussions reach an impasse.”

Security concerns about TikTok’s ownership by a Chinese company were at the center of the executive order Trump signed in August, banning transactions with Beijing-headquartered ByteDance.

The executive order claimed that TikTok posed a threat to national security, though ByteDance maintains that it does not. But in order to prevent the app, which has about 100 million users in the U.S., from being banned, ByteDance reached a deal in September to sell 20% of its stake in TikTok to Oracle and Walmart. With the Biden administration set to take office in January and ByteDance’s ongoing legal challenge against the divestment order, however, the future of the deal is now uncertain.

The new filing is part of a lawsuit TikTok filed against the Trump administration on September 18. It won an early victory when the court stopped the U.S. government’s ban from going into effect on its original deadline that month.

In a statement emailed to TechCrunch, a TikTok spokesperson said it has been working with the CFIUS for a year to address its national security concerns “even as we disagree with its assessment.”

“Facing continual new requests and no clarity on whether our proposed solutions would be accepted, we requested the 30-day extension that is expressly permitted in the August 14 order,” the statement continued.

“Today, with the November 12 CFIUS deadline imminent and without an extension in hand, we have no choice but to file a petition in court to defend our rights and those of our more than 1,500 employees in the US.”

TikTok asks U.S. federal appeals court to vacate U.S. divestment order by TechCrunch on Scribd

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/10/bytedance-asks-federal-appeals-court-to-vacate-u-s-order-forcing-it-to-sell-tiktok/

#HTE

India’s antitrust watchdog has approved Google’s proposed investment of $4.5 billion in the nation’s largest telecom platform Jio Platforms, it said in a tweet on Wednesday.

Google announced in July that it would be investing $4.5 billion for a 7.73% stake in the top Indian telecom network. As part of the deal, Google and Jio Platforms plan to collaborate on developing a customized-version of Android mobile operating system to build low-cost, entry-level smartphones to serve the next hundreds of millions of users, the two companies said.

Jio Platforms is planning to launch as many as 200 million smartphones in the next three years, according to a pitch the telecom giant has made to several developers. These smartphones, as is the case with nearly 40 million of Jio’s feature phones in circulation today, will have an app store with only a few dozen apps, all vetted and approved by Jio, according to one developer who was pitched by Jio Platforms. An industry executive described Jio’s store as a walled garden.

The Indian watchdog, Competition Commission of India (CCI), was said to be interested in reviewing the data sharing agreement between Google and Jio, Indian newspaper Economic Times reported last month, citing an unidentified source.

The announcement today comes days after the CCI announced it had directed an in-depth investigation into Google to verify the allegations of whether the Android-maker promotes its payments service during the installation of an Android smartphone (and whether phone vendors have a choice to avoid this); and if Google Play Store’s billing system is designed “to the disadvantage of both i.e. apps facilitating payment through UPI, as well as users.”

The call for this in-depth investigation was prompted after the CCI concluded in its initial review that requiring Google Pay to be used to buy apps or make in-app payments was an “imposition of unfair and discriminatory condition, denial of market access for competing apps of Google Pay and leveraging on the part of Google,” the watchdog said.

Jio Platforms, which has amassed over 400 million subscribers, has this year raised over $20 billion from 13 high-profile investors including Facebook, which alone invested $5.7 billion into the Indian firm. That deal has also been approved by the CCI. Jio Platforms is a subsidiary of Reliance Industries, India’s most valued firm. It is run by Mukesh Ambani, Asia’s richest man.

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/11/india-approves-googles-4-5-billion-deal-with-reliances-jio-platforms/

#HTE

India’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, which oversees programs beamed on television and theatres in the country, will now also regulate policies for streaming platforms and digital news outlets in a move that is widely believed to kickstart an era of more frequent and stricter censorship on what online services air.

The new rules (PDF), signed by India’s President Ram Nath Kovind this week, might end the years-long efforts by digital firms to self-regulate their own content to avoid the broader oversight that impacts television channels and theatres and whose programs appeared on those platforms. (Streaming platforms may be permitted to continue to self-regulate and report to I&B, similar to how TV channels follow a programming code and their self-regulatory body works with I&B. But there is no clarity on this currently.)

For instance, the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting currently certifies what movies hit the theatres in the country and the scenes they need to clip or alter to receive those certifications. But movies and shows appearing on services like Netflix and Amazon Prime Video did not require a certification and had wider tolerance for sensitive subjects.

The Ministry of Information and Broadcasting has previously also ordered local television channels to not air sensitive documentaries.

India’s Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology previously oversaw online streaming services, but it did not enforce any major changes. The ministry also oversees platforms where videos are populated by users.

Officials of India’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting have previously argued that with proliferation of online platforms in India — there are about 600 million internet users in the country — there needs to be parity between regulations on them and traditional media sources.

“There is definitely a need for a level playing field for all media. But that doesn’t mean we will bring everybody under a heavy regulatory structure. Our government has been focused on ease of doing business and less regulation, but more effective regulation,” said Amit Khare, Secretary of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, earlier this year.

The move by the world’s second largest internet market is bound to make players like Netflix, Amazon Prime Video, Disney’s Hotstar, Times Internet’s MX Player, and dozens of other streaming services and web-based news outlets more cautious about what all they choose to stream and publish on their platforms, an executive with one of the top streaming services told TechCrunch, requesting anonymity.

Netflix, which has poured over half a billion dollars in its India business, declined to comment.

Digital news outlets and platforms that cover “current affairs” will now also be overseen by India’s Ministry of Information and Broadcasting. Over the years, the Indian government has pressured advertisers and indulged in other practices to shape what several news channels show to their audiences.

Information and Broadcasting minister Prakash Javdekar is expected to address this week’s announcement in an hour. We will update the story with additional details.

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/11/indias-broadcasting-ministry-secures-power-to-regulate-streaming-services-online-content/

#HTE

Debates over anti-competitive practices amongst China’s internet firms resurface every year in the lead up to Singles’ Day, a time when online retailers exhaust their resources and deploy sometimes sneaky tactics to attract vendors and shoppers. This year, just a day before the world’s largest shopping festival was scheduled to fall on November 11, China’s market regulator announced a set of draft rules that could rein in the monopolistic behavior of the country’s top internet firms.

Over the years, e-commerce leaders Alibaba, JD.com, Pinduoduo, food delivery platform Meituan, social giant Tencent and other major industry players have been accused of unfair competition to various extent. Behavior targeted by Beijing’s new proposal includes price discrimination among consumers, preferential treatment for merchants who sign exclusive agreements with platforms, and compulsory collection of user data.

Some of China’s largest tech companies saw their shares drop on Tuesday afternoon trading in Hong Kong: Alibaba by 5.1%, JD.com by 8.78%, Meituan by 10.5%, and Tencent by 4.42%.

Meituan, JD.com and Pinduoduo declined to comment on the draft rules. Tencent and Alibaba cannot be immediately reached.

The aim of the regulatory proposal is “to prevent and stop monopolistic practices in internet platforms’ economic activity, to lower compliance costs for law enforcers and business operators, to enhance and improve antitrust regulations on the platform economy, to protect market fairness, to ensure the interests of consumers and society, and to encourage the healthy and continuous development of the platform economy.”

In other words, China wants to restore order in its sprawling internet industry, which has given rise to some of the world’s most valuable companies today. Major laws it weighed in recent years targeting its tech darlings include the e-commerce law passed in 2018 and the data security draft law that was seeking comments earlier this year. Just a few days ago, Beijing abruptly called off Ant Group’s highly anticipated initial public offering, a sign of the authorities’ heightened oversight over the fintech industry.

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/10/china-antitrust-rules-on-internet-industry/

#HTE

Bill Zhang lowered himself into lunges on a squishy mat as he explained to me the benefits of the full-body training suit he was wearing. We were in his small, modest office in Xili, a university area in Shenzhen that’s also home to many hardware makers. The connected muscle stimulator attached to the suit, called Balanx, is designed to bring so-called electronic muscle stimulation, which is said to help improve metabolism and burn fat.

“We are not really aiming at Chinese consumers at this point,” said Zhang, who started Balanx in 2014. “The suit is for the more savvy consumers in the West.”

Prospects for hardware makers were looking bright until two years ago when the Trump administration began setting trade barriers on China. Relations between the two countries have been deteriorating over a series of flashpoint events, from Beijing’s policy on Hong Kong to the coronavirus pandemic.

Chinese entrepreneurs don’t expect relationships between the countries to warm up anytime soon, but many do believe the new office will make “less erratic” and “more rational” policy decisions, according to conversations TechCrunch had with seven Chinese hardware startups. Chinese tech businesses, big or small, are adapting swiftly in the new era of U.S.-China competition as they continue to woo overseas customers.

Designed in China

Zhang is just one of the many entrepreneurs looking to bring state-of-the-art Chinese hardware to the world. This generation of founders no longer hawk cheap electronic copycats, the image attached to the old “Made in China” regime. Decades of knowledge transfer, product development, manufacturing, export practice and policy support have made China a powerhouse for producing new technologies that are both edgy and still widely affordable.

The Balanx smart training suit / Source: Balanx

Anker’s power banks, Roborock’s vacuums and Huami’s fitness trackers are just a few items that have gained loyal followings in several overseas markets, not to mention global household names like Huawei, Xiaomi, Oppo and DJI.

Consumer sentiment is also changing. Europeans’ perception of “Made in China” quality and innovation has “improved significantly” over the last 10 to 15 years, said Frank Wang who oversees marketing at Xiaomi -backed Dreame which makes premium home appliances including cheaper alternatives to Dyson hairdryers and vacuums.

The new players are eager to replicate the success of their predecessors. They seek media attention and retail partners at international trade fairs like CES, teach themselves Facebook and Google campaigns, and court gadget lovers on crowdfunding platforms. Investors ranging from GGV Capital to Xiaomi rush to back scrappy startups that are already shipping millions of units around the globe.

For Donny Zhang, a Shenzhen-based electronics parts supplier to hardware companies, businesses have been shrinking as soon as the trade war began. “My clients are taking the brunt because the costs of procurement have increased,” he said of those who directly or indirectly deal with American firms.

While many export-led hardware businesses loathe decreasing profitability, some learn to adapt and look for a silver lining. That has unexpectedly spurred new directions for factory owners in China. Indiegogo, one of the world’s largest crowd-funding platforms, saw the changes first hand.

“Once tariffs increase, there’s not much profit margin left for manufacturers because the middlemen already eat up the bulk of their profit,” Lu Li, general manager for Indiegogo’s global strategy, told TechCrunch.

“A good solution is for factories to skip the middlemen and sell directly to consumers with their own brands. Once the goal of brand building is clear, they often come to us because they need marketing help as a first step to establish themselves as a global consumer brand.”

The trend, dubbed “direct-to-consumers” or D2C, also plays into China’s national plan to encourage manufacturing upgrade and homegrown innovations to compete globally, an initiative that began to take shape around 2015. The development naturally makes China Indiegogo’s fastest-growing region in the last two years: in the first three quarters of 2020, businesses coming from China jumped 50% year-over-year, according to Li.

Localize

Having an appealing product and brand is just the prerequisite. Ever-changing trade policies and geopolitics have forced many Chinese businesses to localize seriously, whether that means setting up a foreign entity or building a local team.

Dreame’s wireless vacuum / Source: Dreame

For Tuya, which provides IoT solutions to device makers around the world, the trade war’s effect has been “minimal” since it has operated a U.S. entity since 2015, which employs its local sales and technical support staff. Most of its research and development, however, still lies in the hands of its engineers in India and China, the latter of which can be a potential contention point, as shown by TikTok’s recent backlash in the U.S.

“The key is compliance. We have a dedicated team of security experts to work on compliance issues. For instance, we were one of the first to get GDPR certified in Europe,” said the company’s chief marketing office Eva Na.

The company’s readiness is prompted by practical needs though. Many of its clients are large Western corporations that demand strict legal compliance in vendors, so Tuya began collecting the needed certificates early on. Connecting 200,000 SKUs today, Tuya’s footprint is found in over 190 overseas countries, which account for over 60% of its business.

Well-funded Tuya may have the financial and operational capacity to sustain an overseas team; but for smaller startups, localization can be a costly and tedious learning curve. Many opted to set up a Hong Kong entity to tap the city’s status as a global financial hub and evade trade restrictions on China, an advantage of the territory that began to crumble following Beijing’s implementation of the national security law.

Balanx, the smart training suit maker, has a Hong Kong entity like many of its export-facing hardware peers. To cope with new global headwinds, it registered a virtual company in Nevada but quickly realized the entity is of little use unless it has an on-the-ground operation in the U.S.

“Many local banks would ask for utility bills and etc. if I want to open an account, which we don’t have. We realized we must have a local team,” asserted the founder.

Hope

Zhang is positive that small companies like his own will remain under the radar in spite of U.S. sanctions. “Just avoid having any government connection,” he said.

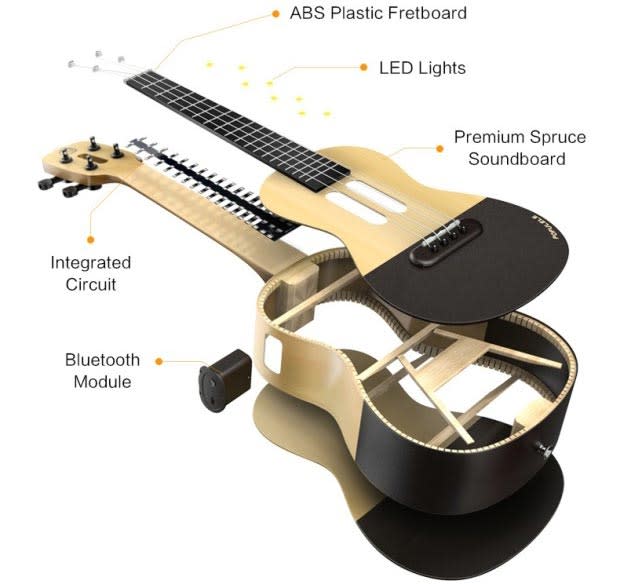

Populele, PopuMusic’s smart ukulele / Source: PopuMusic

Indeed, some of the more “benign” and niche products are continuing to thrive in their global push. PopuMusic, a Xiaomi-backed startup making smart instruments like ukulele and guitar to teach beginners, is one. “We aren’t affected by the trade war. We are in a business that’s neither threatening nor aggressive,” said Zhang Bohan, founder of PopuMusic, which counts the U.S. as one of its biggest overseas markets.

Chinese brands are also seeing their edge as the coronavirus sweeps across the globe and confines millions at home. Hardware makers like Balanx, Dreame and PopuMusic have long learned to master e-commerce and logistics in a country where online shopping is ubiquitous.

“Consumers in Europe and the U.S. are growing more accustomed to e-commerce, a bit like those in China five to eight years ago,” said Wang of Dreame.

Rather than rethinking the U.S., PopuMusic is forging further ahead by launching a new connected guitar via an Indiegogo campaign. Global expansion is at the core of the startup’s vision, the founder said. “We are global from day one. We had an English name before even coming up with a Chinese one.”

In the process of making big bucks, hardware makers may have to downplay their “Made in China” or “Designed in China” brand, said Li of Indiegogo. This could help them avoid unnecessary geopolitical complications and attention in their international push. But one has to wonder how this new generation of entrepreneurs is reckoning with their national pride. How do they deal with the mission passed down by Beijing to promote Chinese innovation in the global marketplace? It’s a line that Chinese entrepreneurs have to tread carefully in their global journey in the years to come.

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/09/chinese-hardware-global-expansion-geopolitics/

#HTE

As Ant Group seizes the world’s attention with its record initial public offering, which was abruptly called off by Beijing, investors and analysts are revisiting Tencent’s fintech interests, recognized as Ant’s archrival in China.

It’s somewhat complicated to do this, not least because they are sprawled across a number of Tencent properties and, unlike Ant, don’t go by a single brand or operational structure — at least, not one that is obvious to the outside world.

However, when you tease out Tencent’s fintech activity across its wider footprint — from direct operations like WeChat Pay through to its sizeable strategic investments and third-party marketplaces — you have something comparable in size to Ant, and in some services even bigger.

Hidden business

Ant refuted the comparison with Tencent or anyone else. In a reply to China’s securities regulator in September, the Jack Ma-controlled, Alibaba-backed fintech giant said it is “not comparable” to WeChat Pay, the fintech tool inside WeChat, Tencent’s flagship messenger.

“In the space of digital payments and merchant service, there are many players around the world, including Tencent’s WeChat Pay. But the payments services offered by these companies are different from our digital payments and merchant services. They are not comparable. In terms of digital finance, our way of working with and serving financial institutions, as well as our revenue model, are novel and do not have a counterpart,” the company noted in a somewhat hubristic reply.

There’s no denying that Ant is a pioneer in expanding financial inclusion in China, where millions remain outside the formal banking system. But Tencent has played catch-up in digital finance and made major headway, especially in electronic payments.

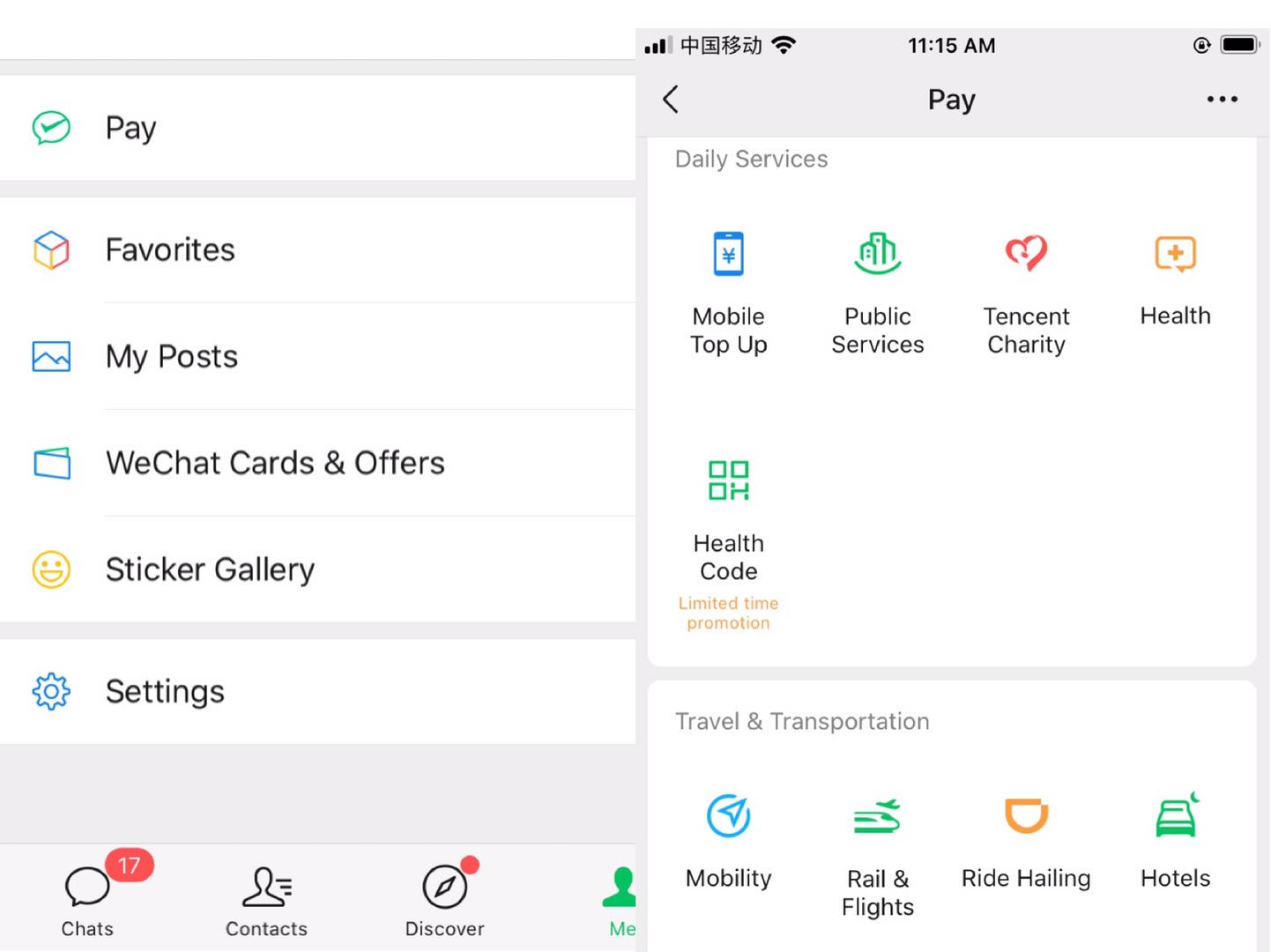

Both companies ventured into fintech by first offering consumers a way to pay digitally, though the brands “Alipay” and “WeChat Pay” fail to reflect the breadth of services touted by the platforms today. Alipay, Ant’s flagship app, is now a comprehensive marketplace selling Ant’s in-house products and myriad third-party ones like micro-loans and insurance. The app, like WeChat Pay, also facilitates a growing list of public services, letting users see their taxes, pay utility bills, book a hospital visit and more.

Screenshots of the Alipay app. Source: iOS App Store

Tencent, on the other hand, embeds its financial services inside the payment features of WeChat (WeChat Pay) and the giant’s other popular chat app, QQ. It has thus been historically difficult to make out how much Tencent earns from fintech, something the giant doesn’t disclose in its earnings reports. This is reflective of Tencent’s “horse racing” internal competition, in which departments and teams often rival fiercely against each other rather than actively collaborate.

Screenshots of WeChat Pay inside Tencent’s WeChat messenger

As such, we have pulled together estimates of Tencent’s fintech businesses ourselves using a mix of quarterly reports and third-party research — a mark of how un-transparent some of this really is — but it begs some interesting questions. Will (should?) Tencent at some point follow in Alibaba’s footsteps to bring its own fintech operations under one umbrella?

User number

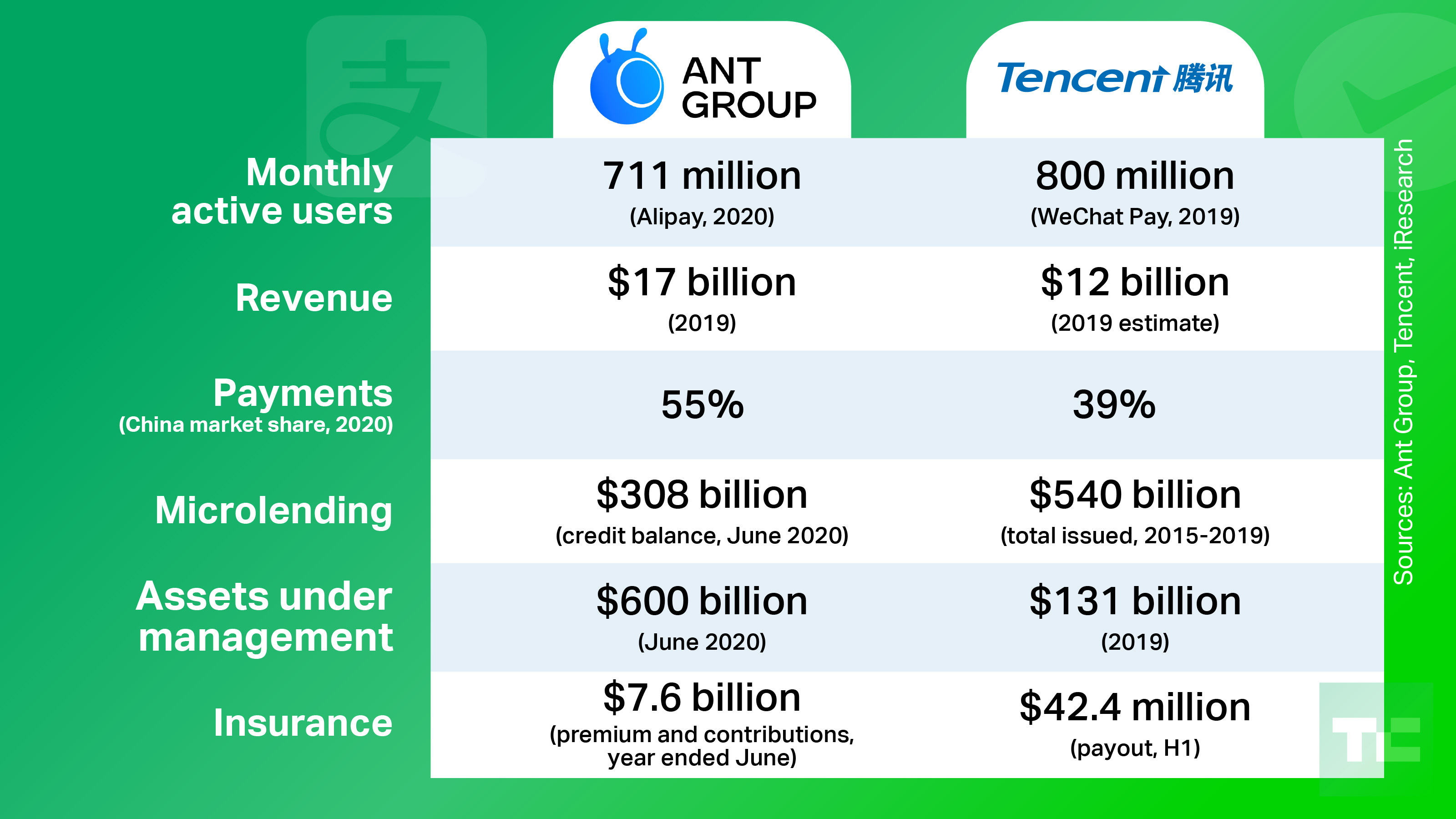

In terms of user size, the rivals are going neck and neck.

The Alipay app recorded 711 monthly active users and 80 million monthly merchants in June. Among its 1 billion annual users, 729 million had transacted in at least one “financial service” through the platform. As in the PayPal-eBay relationship, Alipay benefits tremendously by being the default payments processor for Alibaba marketplaces like Taobao.

As of 2019, more than 800 million users and 50 million merchants used WeChat to pay monthly, a big chunk of the 1.2 billion active user base of the messenger. It’s unclear how many people tried Tencent’s other fintech products, though the firm did say about 200 million people used its wealth management service in 2019.

Revenue

Ant reported a total of 121 billion yuan or $17 billion in revenue last year, nearly doubling its sum from 2017 and putting it on par with PayPal at $17.8 billion.

In 2019, Tencent generated 101 billion yuan of revenue from its “fintech and business services. The segment mainly consisted of fintech and cloud products, industry analysts told TechCrunch. With its cloud unit finishing the year at 17 billion yuan in revenue, we can venture to estimate that Tencent’s fintech products earned roughly or no more than 84 billion yuan ($12 billion), from the period — paled by Ant’s figure, but not bad for a relative latecomer.

The sheer size of the fintech giants has made them highly attractive targets of regulation. Increasingly, Ant is downplaying its “financial” angle and billing itself as a “technology” ally for traditional institutions rather than a challenger. These days, Alipay relies less on selling proprietary financial products and bills itself as an intermediary helping state banks, wealth managers and insurers to reach customers. In return for facilitating the process, Ant charges administrative fees from transactions on the platform.

Now, let’s turn to the rivals’ four main business focuses: payments, microloans, wealth management and insurance.

Ant vs. Tencent’s fintech businesses. Sources for the figures are companies’ quarterly reports, third-party research and TechCrunch estimates.

Digital payments

In the year ended June, Alipay processed a whopping 118 trillion yuan in payment transactions in China. That’s about $17 trillion and dwarfs the $172 billion that PayPal handled in 2019.

Tencent doesn’t disclose its payments transaction volume, but data from third-party research firms offer a hint of its scale. The industry consensus is that the two collectively control over 90% of China’s trillion-dollar electronic payments market where Alipay enjoys a slight lead.

Alipay processed 55.4% of China’s third-party payments transactions in the first quarter of 2020, according to market research firm iResearch, while another researcher Analysys said the firm’s share was 48.44% in the period. In comparison, Tenpay (the brand assigned to the company-wide infrastructure that powers WeChat Pay and the less-significant QQ Wallet, yet another name to confuse people) trailed behind at 38.8%, per iResearch data, and 34% according to Analysys.

At the end of the day, the two services have distinct user scenarios. The fact that WeChat Pay lies inside a messenger makes it a tool for social, often small, payments, such as splitting bills and exchanging lucky money, a custom in China. Alipay, on the other hand, is associated with online shopping.

That’s changing as Tencent tries to increase its ticket size through alliances. It’s tied WeChat Pay to portfolio e-commerce companies like JD.com, Pinduoduo and Meituan — all Alibaba’s competitors.

Third-party payments were once an incredibly profitable business. Platforms used to be able to hold customer reserve funds from which they generated handsome interests. That lucrative scheme came to a stop when Chinese regulators demanded non-bank payments providers to place 100% of customer deposit funds under a centralized, interest-free account last year. What’s left for payment processors to earn are limited fees charged from merchants.

Payments still account for the bulk of Ant’s revenues — 43%, or a total of 51.9 billion yuan ($7.6 billion) in 2019, but the percentage was down from 55% in 2017, a sign of the giant’s diversifying business.

Microlending

Ant has become the go-to lender for shoppers and small businesses in a country where millions aren’t qualified for bank-issued credit cards. The firm had worked with about 100 banks, doling out 1.7 trillion yuan ($250 billion) of consumer loans and 400 billion yuan ($58 billion) of small business loans in the year ended June. That amounted to 41.9 billion yuan or 34.7% of Ant’s annual revenue.

The size of Tencent’s loan business is harder to gauge. What we do know is that Weilidai, the microloan product sold through WeChat, had issued an aggregate of 3.7 trillion yuan ($540 billion) to 28 million customers between its launch in 2015 and 2019, according to a report from WeBank, the Tencent-backed private bank that provides the WeChat-based loan.

Wealth management

As of June, Ant had 4.1 trillion yuan ($600 billion) assets under management, making it one of the world’s biggest money-market funds. Working with 170 partner asset managers, the segment brought in about 17 billion yuan or 14% of total revenue in 2019.

Tencent said its wealth management platform accumulated assets of over 600 billion yuan in 2018 and grew by 50% year-over-year in 2019. That should put its AUM in 2019 at around 900 billion yuan ($131 billion).

Insurance

Last but not least, both giants have made big pushes into consumer insurance. Besides featuring third-party plans, Alipay introduced a new way to insure customers: mutual aid. The novel scheme, which is not regulated as an insurance product in China, is free to sign up and does not charge any premium or upfront payment. Users pay small monthly fees that are pooled to pay for claims of critical illnesses.

Insurance premiums and mutual aid contributions on Ant’s platform reached 52 billion yuan, or $7.6 billion, in the year ended June. Working with about 90 partner insurers in China, the segment contributed nearly 9 billion yuan, or 7.4%, of the firm’s annual revenue. More than 570 million Alipay users participated in at least one insurance program in the year ended June.

Tencent, on the other hand, taps partners in its relatively uncharted territory. Its insurance strategy includes in-house platform WeSure that works like a middleman between insurers and consumers, and Tencent-backed Waterdrop, which provides both traditional insurances and a rival to Ant’s mutual aid product Xianghubao.

In the first half of 2020, WeSure, Tencent’s main insurance operation that sells through WeChat, paid out a total of 290 million yuan ($42.4 million), it announced. The unit does not disclose its amount of premiums or revenues, but we can find clues in other figures. Twenty-five million people used WeShare services in 2019 and the average premium amount per user was over 1,000 yuan ($151). That is, WeShare generated no more than 25 billion yuan, or $3.78 billion, in premium that year because the user figure also accounts for a good number of premium-free users.

*

Moving forward, it remains unclear whether Tencent will restructure its fintech operations in a more cohesive and collaborative way. As they expand, will investors and regulators demand that? And what opportunities are there for others to compete in a space dominated by two huge players?

One thing is for sure: Tencent will need to tread more carefully on regulatory issues. Ant’s achievement is a win for entrepreneurs looking to “disrupt” China’s financial sector, but its halted IPO, which is tied to regulatory issues and reportedly Jack Ma’s hubris, also sounds an alarm to contenders that policymaking in China can be capricious.

https://techcrunch.com/2020/11/09/tencent-vs-alibaba-ant-fintech/