#HTE

Smart cities are designed to make life easier for their residents: better traffic management by clearing routes, making sure the public transport is running on time and having cameras keeping a watchful eye from above.

But what happens when that data leaks? One such database was open for weeks for anyone to look inside.

Security researcher John Wethington found a smart city database accessible from a web browser without a password. He passed details of the database to TechCrunch in an effort to get the data secured.

The database was an Elasticsearch database, storing gigabytes of data — including facial recognition scans on hundreds of people over several months. The data was hosted by Chinese tech giant Alibaba. The customer, which Alibaba did not name, tapped into the tech giant’s artificial intelligence-powered cloud platform, known as City Brain.

“This is a database project created by a customer and hosted on the Alibaba Cloud platform,” said an Alibaba spokesperson. “Customers are always advised to protect their data by setting a secure password.”

“We have already informed the customer about this incident so they can immediately address the issue. As a public cloud provider, we do not have the right to access the content in the customer database,” the spokesperson added. The database was pulled offline shortly after TechCrunch reached out to Alibaba.

But while Alibaba may not have visibility into the system, we did.

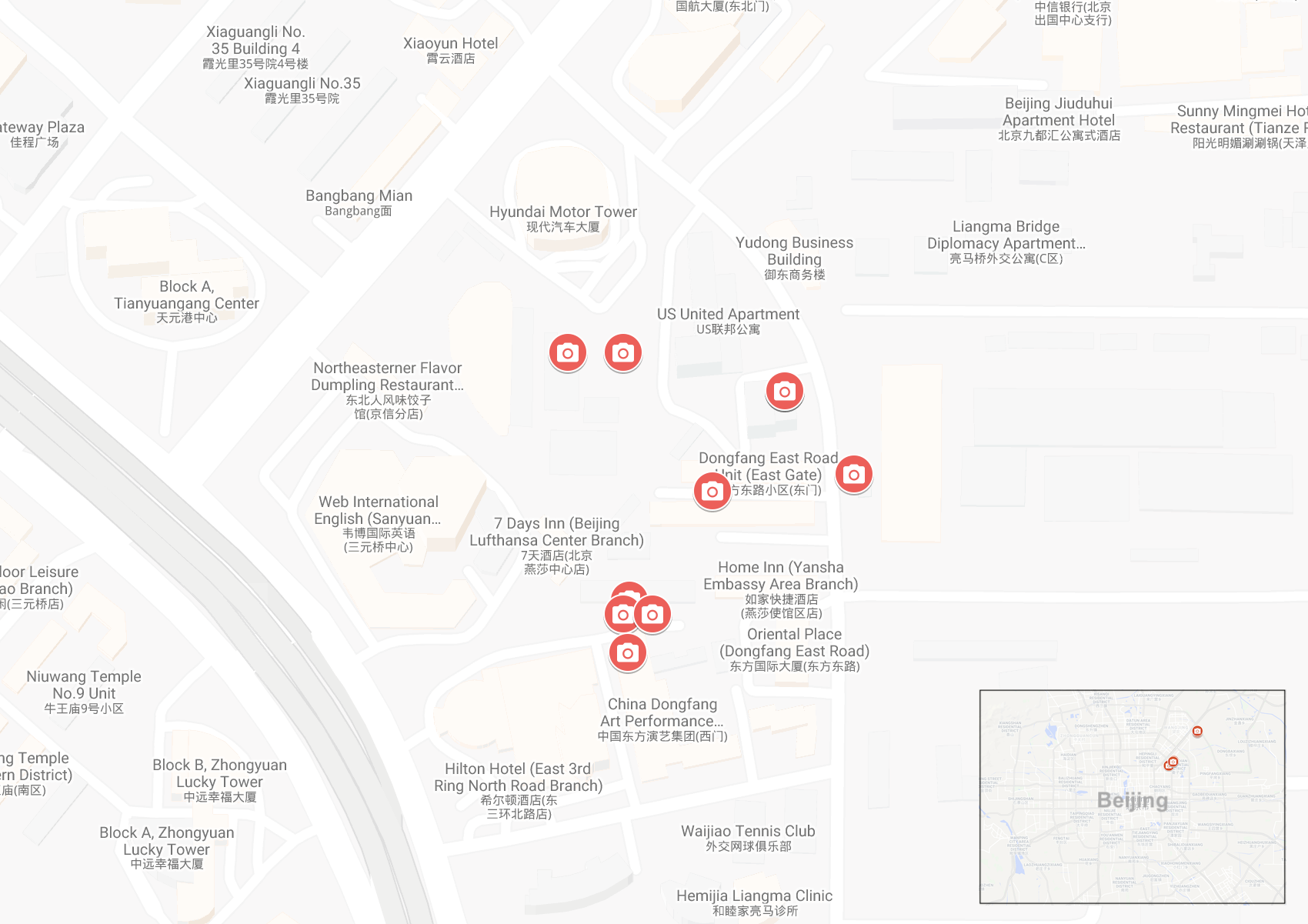

The location of the smart city’s many cameras in Beijing (Image: supplied)

While artificial intelligence-powered smart city technology provides insights into how a city is operating, the use of facial recognition and surveillance projects have come under heavy scrutiny from civil liberties advocates. Despite privacy concerns, smart city and surveillance systems are slowly making their way into other cities both in China and abroad, like Kuala Lumpur, and soon the West.

“It’s not difficult to imagine the potential for abuse that would exist if a platform like this were brought to the U.S. with no civilian and governmental regulations or oversight,” said Wethington. “While businesses cannot simply plug in to FBI data sets today it would not be hard for them to access other state or local criminal databases and begin to create their own profiles on customers or adversaries.”

We don’t know the customer of this leaky database, but its contents offered a rare insight into how a smart city system works.

The system monitors the residents around at least two small housing communities in eastern Beijing, the largest of which is Liangmaqiao, known as the city’s embassy district. The system is made up of several data collection points, including cameras designed to collect facial recognition data.

The exposed data contains enough information to pinpoint where people went, when and for how long, allowing anyone with access to the data — including police — to build up a picture of a person’s day-to-day life.

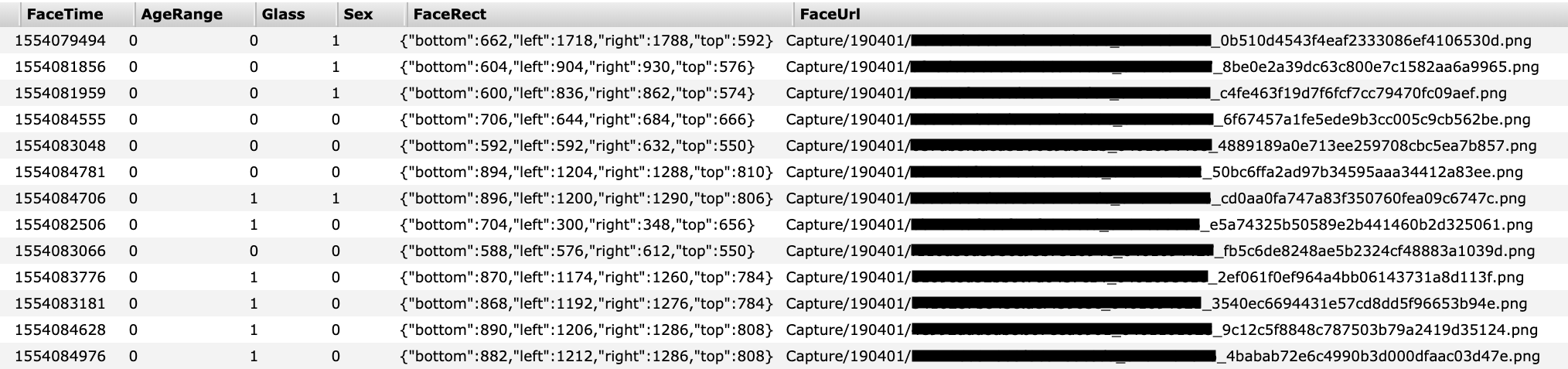

A portion of the database containing facial recognition scans (Image: supplied)

Alibaba provides technologies like City Brain to customers to understand the data they collect from various sources, including license plate readers, door access controls, smart things and internet-connected devices and facial recognition.

Using City Brain’s data-crunching back-end, the cameras can process various facial details, such as if a person’s eyes or mouth are open, if they’re wearing sunglasses, or a mask — common during periods of heavy smog — and if a person is smiling or even has a beard.

The database also contained a subject’s approximate age as well as an “attractive” score, according to the database fields.

But the capabilities of the system have a darker side, particularly given the complicated politics of China.

The system also uses its facial recognition systems to detect ethnicities and labels them — such as “汉族” for Han Chinese, the main ethnic group of China — and also “维族” — or Uyghur Muslims, an ethnic minority under persecution by Beijing.

Where ethnicities can help police identify suspects in an area even if they don’t have a name to match, the data can be used for abuse.

The Chinese government has detained more than a million Uyghurs in internment camps in the past year, according to a United Nations human rights committee. It’s part of a massive crackdown by Beijing on the ethnic minority group. Just this week, details emerged of an app used by police to track Uyghur Muslims.

We also found that the customer’s system also pulls in data from the police and uses that information to detect people of interest or criminal suspects, suggesting it may be a government customer.

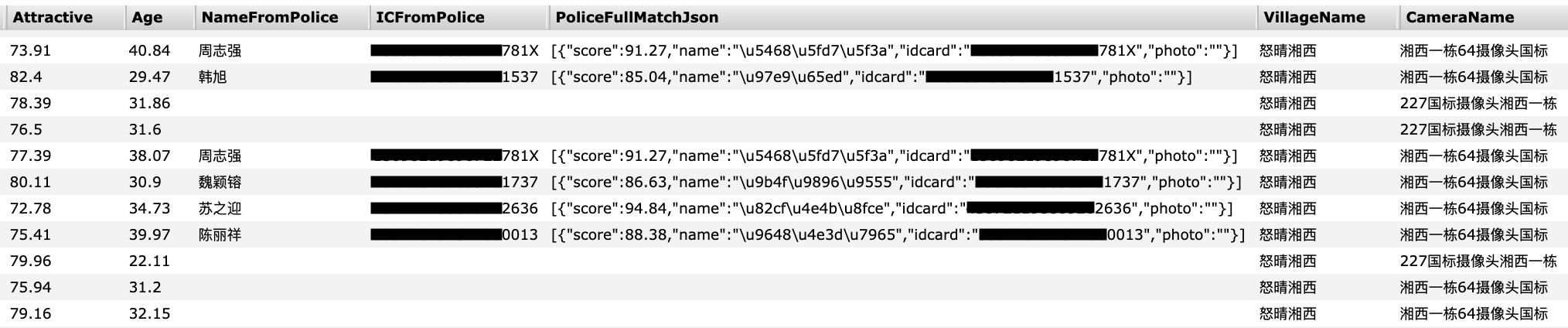

Facial recognition scans would match against police records in real time (Image: supplied)

Each time a person is detected, the database would trigger a “warning” noting the date, time, location and a corresponding note. Several records seen by TechCrunch include suspects’ names and their national identification card number.

“Key personnel alert by the public security bureau: “[name] [location]” – 177 camera detects key individual(s),” one translated record reads, courtesy of TechCrunch’s Rita Liao. (The named security bureau is China’s federal police department, the Ministry of Public Security.)

In other words, the record shows a camera at a certain point detected a person’s face whose information matched a police watchlist.

Many of the records associated with a watchlist flag would include the reason why, such as if a recognized person was a “drug addict” or “released from prison.”

The system is also programmed to alert the customer in the event of building access control issues, smoke alarms and equipment failures — such as when cameras go offline.

The customer’s system also has the capability to monitor for Wi-Fi-enabled devices, such as phones and computers, using sensors built by Chinese networking tech maker Renzixing and placed around the district. The database collects the dates and times that pass through its wireless network radius. Fields in the Wi-Fi-device logging table suggest the system can collect IMEI and IMSI numbers, used to uniquely identify a cellular user.

Although the customer’s smart city system was on a small scale with only a few dozen sensors, cameras and data collection points, the amount of data it collected in a short space of time was staggering.

In the past week alone, the database had grown in size — suggesting it’s still actively collecting data.

“The weaponization and abuse of A.I. is a very real threat to the privacy and security of every individual,” said Wethington. “We should carefully look at how this technology is already being abused by other countries and businesses before permitting them to be deployed here.”

It’s hard to know if facial recognition systems like this are good or bad. There’s no real line in the sand separating good uses from bad uses. Facial and object recognition systems can spot criminals on the run and detect weapons ahead of mass shootings. But some worry about the repercussions of being watched every day — even jaywalkers don’t get a free pass. The pervasiveness of these systems remain a privacy concern for civil liberties groups.

But as these systems develop and become more powerful and ubiquitous, companies might be better placed to first and foremost make sure its massive data banks don’t inadvertently leak.

https://techcrunch.com/2019/05/03/china-smart-city-exposed/