#HTE

Artificial intelligence is widely heralded as something that could disrupt the jobs market across the board — potentially eating into careers as varied as accountants, advertising agents, reporters and more — but there are some industries in dire need of assistance where AI could make a wholly positive impact, a core one being healthcare.

Despite being the world’s second-largest economy, China is still coping with a serious shortage of medical resources. In 2015, the country had 1.8 physicians per 1,000 citizens, according to data compiled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. That figure puts China behind the U.S. at 2.6 and was well below the OECD average of 3.4.

The undersupply means a nation of overworked doctors who constantly struggle to finish screening patient scans. Misdiagnoses inevitably follow. Spotting the demand, forward-thinking engineers and healthcare professionals move to get deep learning into analyzing medical images. Research firm IDC estimates that the market for AI-aided medical diagnosis and treatment in China crossed 183 million yuan ($27 million) in 2017 and is expected to reach 5.88 billion yuan ($870 million) by 2022.

One up-and-comer in the sector is 12 Sigma, a San Diego-based startup founded by two former Qualcomm engineers with research teams in China. The company is competing against Yitu, Infervision and a handful of other well-funded Chinese startups that help doctors detect cancerous cells from medical scans. Between January and May last year alone, more than 10 Chinese companies with such a focus scored fundings of over 10 million yuan ($1.48 million), according to startup data provider Iyiou. 12 Sigma itself racked up a 200 million yuan Series B round at the end of 2017 and is mulling a new funding round as it looks to ramp up its sales team and develop new products, the company told TechCrunch.

“2015 to artificial intelligence is like 1995 to the Internet. It was the dawn of a revolution,” recalled Zhong Xin, who quit his management role at Qualcomm and went on to launch 12 Sigma in 2015. At the time, AI was cereping into virtually all facets of life, from public security, autonomous driving, agriculture, education to finance. Zhong took a bet on health care.

“For most industries, the AI technology might be available, but there isn’t really a pressing problem to solve. You are creating new demand there. But with healthcare, there is a clear problem, that is, how to more efficiently spot diseases from a single image,” the chief executive added.

An engineer named Gao Dashan who had worked closely with Zhong at Qualcomm’s U.S. office on computer vision and deep learning soon joined as the startup’s technology head. The pair both attended China’s prestigious Tsinghua University, another experience that boosted their sense of camaraderie.

Aside from the potential financial rewards, the founders also felt an urge to start something on their own as they entered their 40s. “We were too young to join the Internet boom. If we don’t create something now for the AI era, it will be too late for us to be entrepreneurs,” admitted Zhong who, with age, also started to recognize the vulnerability of life. “We see friends and relatives with cancers get diagnosed too late and end up The more I see this happen, the more strongly I feel about getting involved in healthcare to give back to society.”

A three-tier playbook

12 Sigma and its peers may be powering ahead with their advanced imaging algorithms, but the real challenge is how to get China’s tangled mix of healthcare facilities to pay for novel technologies. Infervision, which TechCrunch wrote about earlier, stations programmers and sales teams at hospitals to mingle with doctors and learn their needs. 12 Sigma deploys the same on-the-ground strategy to crack the intricate network.

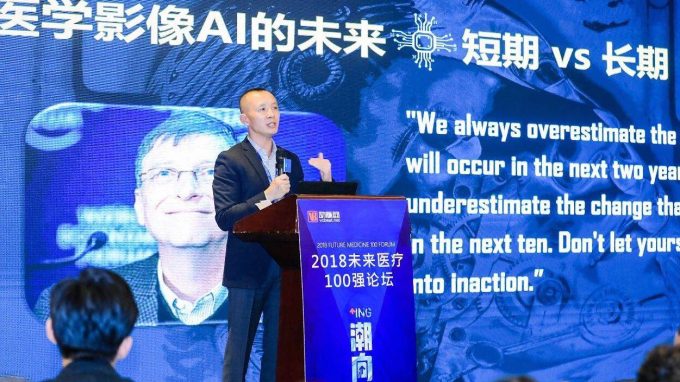

Zhong Xin, Co-founder and CEO of 12 Sigma / Photo source: 12 Sigma

“Social dynamics vary from region to region. We have to build trust with local doctors. That’s why we recruit sales persons locally. That’s the foundation. Then we begin by tackling the tertiary hospitals. If we manage to enter these hospitals,” said Zhong, referring to the top public hospitals in China’s three-tier medical system. “Those partnerships will boost our brand and give us greater bargaining power to go after the smaller ones.”

For that reason, the tertiary hospitals are crowded with earnest startups like 12 Sigma as well as tech giants like Tencent, which has a dedicated medical imaging unit called Miying. None of these providers is charging the top boys for using their image processors because “they could easily switch over to another brand,” suggested Gao.

Instead, 12 Sigma has its eyes on the second-tier hospitals. As of last April, China had about 30,000 hospitals, out of which 2,427 were rated tertiary, according to a survey done by the National Health and Family Planning Commission. The second tier, serving a wider base in medium-sized cities, had a network of 8,529 hospitals. 12 Sigma believes these facilities are where it could achieve most of its sales by selling device kits and charging maintenance fees in the future.

The bottom tier had 10,135 primary hospitals, which tend to concentrate in small towns and lack the financial capacity to pay the one-off device fees. As such, 12 Sigma plans to monetize these regions with a pay-per-use model.

So far, the medical imaging startup has about 200 hospitals across China testing its devices — for free. It’s sold only 10 machines, generating several millions of yuan in revenue, while very few of its rivals have achieved any sales at all according to Gao. At this stage, the key is to glean enough data so the startup’s algorithms get good enough to convince hospital administrators the machines are worth the investment. The company is targeting 100 million yuan ($14.8 million) in sales for 2019 and aims to break even by 2020.

China’s relatively lax data protection policy means entrepreneurs have easier access to patient scans compared to their peers in the west. Working with American hospitals has proven “very difficult” due to the country’s privacy protection policies, said Gao. They also come with a different motive. While China seeks help from AI to solve its doctor shortage, American hospitals place a larger focus on AI’s economic returns.

“The healthcare system in the U.S. is much more market-driven. Though doctors could be more conservative about applying AI than those in China, as soon as we prove that our devices can boost profitability, reduce misdiagnoses and lower insurance expenditures, health companies are keen to give it a try,” said Gao.

https://techcrunch.com/2019/02/10/12-sigma-profile/