#HTE

LinkedIn’s China site looks and functions just like LinkedIn everywhere else, except now it asks users in the country to verify their identities through phone numbers.

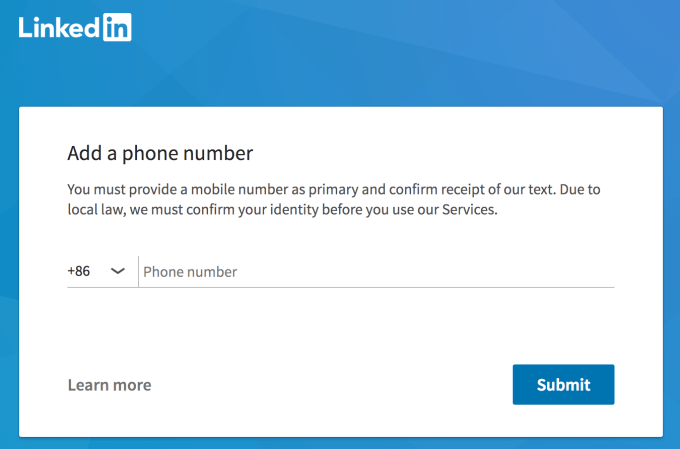

The American company is requiring both new and existing users with a Chinese IP address to link mobile phone numbers to their accounts, TechCrunch noticed this week. LinkedIn had for months told its China-based users to provide mobile number details before sending them to the main page, but it had mercifully kept a little “Skip” button that let users avoid the fuss until at least last week.

“The real-name verification process for our LinkedIn China members is a legal requirement, which will also help improve the authenticity and credibility of online accounts,” a LinkedIn China spokesperson wrote back to TechCrunch in an email without addressing whether the process is new.

The spokesperson also links the policy to China’s burgeoning mobile industry: “Considering the growing popularity of mobile devices and mobile Internet, Chinese Internet users are adapted to registration with mobile phone numbers instead of email addresses. Almost all apps in the Chinese market are applying this trend to follow users’ habits.”

LinkedIn users with a Chinese IP address are greeted with an identity check tied to phone numbers. Screenshot: TechCrunch

In a note visible to China-based users only, LinkedIn explains that its identity check is a response to local regulations:

In some countries, local laws require that we confirm your identity before letting you engage with our Services. You must provide a mobile number and confirm receipt of our text. This phone number will be associated with your account and is accessible from your settings. If you choose to change or delete your confirmed mobile number your ability to access our Services in certain countries (e.g. China) will be blocked until you once again confirm your identity.

The California-based social network for professionals is a rare existence in China, where most mainstream global tech services like Facebook and Google have long remained blocked. Exceptions happen when foreign players bend to local rules. Microsoft’s Bing is accessible in China by censoring search results. Google also reportedly mulled a censored search service to re-enter China, an attempt that outraged its staff, politicians and speech advocates.

LinkedIn, which launched in China back in 2014, also hires so-called “information auditors” to keep close tabs on what users say and share in its China realm, according to a job post the firm listed on a local recruiting site. Like Google, LinkedIn caught flack for censoring content.

Real identity

Digital anonymity came to an end in China — at least in theory — when the sweeping Cyberspace Law took effect in 2017. The rules, which are meant to police information on the web, ordered websites to verify users’ real identities before letting them comment or use other tools, though users can still post with their screen names.

Large platforms like messenger WeChat and Twitter -like Weibo reacted swiftly by running real-name checks on users. The staple practice is to collect mobile phone numbers, which became a form of ID after China introduced a policy in 2010 requiring all buyers, foreign or Chinese, to show a piece of identification when they obtain their 11-digit identifiers. Google’s rumored search engine for China also asked for users’ phone numbers, according to The Intercept, which would make it easier for the government to monitor people’s queries.

LinkedIn’s China office in Beijing. Photo: LinkedIn China via Weibo

LinkedIn had been able to avoid the inevitable process for months. Perhaps the government had gone after the biggies first. After all, LinkedIn is only a fraction the size of its main rival in China. As of November, LinkedIn had 13 million monthly installs while its local peer Maimai had 95 monthly installs, data from iResearch shows. Both are dwarfed by WeChat’s more than 1 billion monthly active users.

As with other fledgling industries, laws often lag behind technological development, not to mention the enforcement thereof when the odds are against enterprises. Take ride-hailing for example. Unlicensed drivers and vehicles were still running on the roads two years after China legalized the sector. When the government steps up oversight recently, the market is hit by a shortage of drivers.

Clamping down

TechCrunch has come to understand that LinkedIn’s identity enforcement is linked to the latest wave of government crackdowns. “Slowly, the Chinese Communist Party has been pushing their collective thumbs down on, not only foreign internet companies but all internet companies. It just so happens that the recent political atmosphere is causing more scrutiny,” a source with insights into the matter told TechCrunch, asking not to be named.

Other websites are also indeed tightening controls over users. Many apps that previously allowed third-party logins from platforms like WeChat and Weibo also recently started collecting users’ phone numbers, several people who experienced the changes told TechCrunch.

Users can still get around LinkedIn’s real-name verification by switching on their virtual private network, known as VPN, that lets people surf the net from an overseas IP address and circumvent the Great Firewall, China’s internet censoring machinery. But the practice is becoming more challenging and the stakes are growing. By law, only government-approved providers can set up VPNs. In response to regulatory oversight, Apple pulled hundreds of VPN apps from its China App Store in 2017.

More recently, China’s telecoms regulator slapped a 1,000 yuan (around $146) fine on a man for accessing the “international net” through “illegal channels.” The case is one of the few known instances where individuals are punished for using VPNs, sending worrying signs to those jumping the Wall to surf the unfiltered world wide web.

https://techcrunch.com/2019/01/09/linkedin-real-name-phone-number-verification-china/