#HTE

In the Kiki Ballroom Scene, Queer Kids of Color Can Be Themselves (22 photos)

Every year, thousands of LGBTQ teens are forced to leave their home. Though data are sparse, studies have found that when gay teens come out to their family, about a quarter are kicked out, and a third are assaulted by parents or caregivers. Life can be even harder for LGBTQ youth of color, who say they’re the frequent target of racial discrimination and harassment in schools and communities. Homelessness puts these kids at higher risk for HIV, survival sex work, and run-ins with the police, with some activists estimating that up to half the members of the kiki community are HIV-positive. Traumatized, isolated, and abandoned, many of these teens and young adults set out in search of New York City’s legendary kiki scene, a close-knit community of mostly black and Latinx LGBTQ youth, some as young as 13 years old.

In the face of these challenges, members of the kiki scene turn to one another for support, forging a surrogate-family structure that promises radical acceptance. The kiki scene traces its roots to 1920’s ballroom culture, an underground community that emerged in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance as a safe space for queer people of color. In the 1980s, ballroom culture gained broader national attention when the HIV/AIDS crisis led its members to start advocating for greater visibility, acceptance, and support. Today ballroom culture is best known for the voguing dance style replicated by Madonna in her 1990 music video “Vogue.” By the 2000s, activists from the Ballroom scene recognized the need to create a space for LGBTQ Millennials of color, many of whom were homeless and desperately in need of HIV-prevention services. A small group of activists—including Diori, leaders of the Gay Men’s Health Crisis, and influential teens and young adults—helped to pioneer the kiki scene, which borrows from the legacy of traditional ballroom culture but insists on a youth-focused leadership and cultural identity.

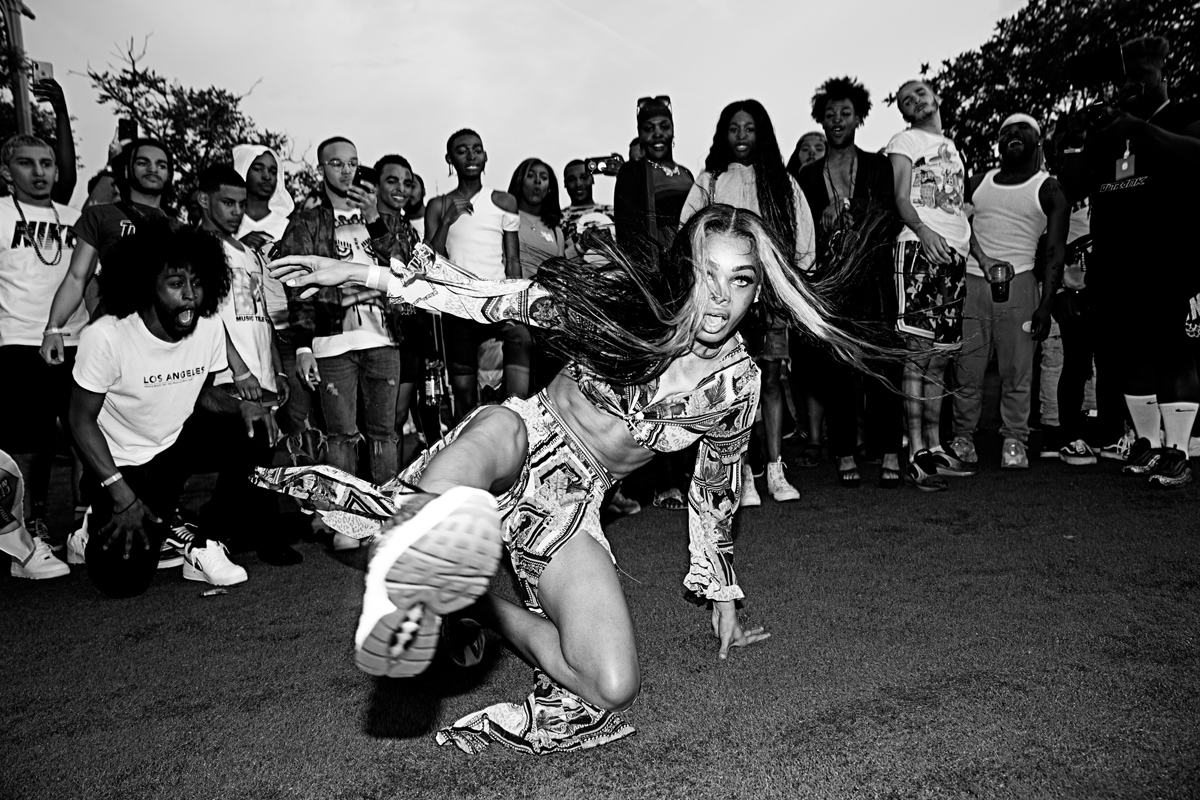

Now, almost 20 years later, LGBTQ youth continue to seek refuge in the community. Today there are about a dozen active kiki “houses” in New York City, each composed of a “mother, ” a “father,” and a gaggle of “children.” Every month, kiki house members get together for extravagant competitions known as balls: joyous, raucous affairs where house members vie for trophies and cash prizes in a series of runway competitions and performance-art battles. Balls are infused with safe-sex messaging and typically offer free HIV testing. They provide an alternative to high-risk behavior for troubled youth. Membership in a kiki house is a huge responsibility—members are expected to show up for weekly rehearsals and meetings, even as they struggle with HIV and homelessness.

Many members of the kiki scene, such as Zay, Dynasty and Aniyah, who you’ll meet in this essay, have worked their way up through its ranks and now act as house mothers and fathers, helping a younger generation navigate the challenges of being a queer kid of color. They’re activists and advocates, modeling good behavior and offering a stable support structure for the children of their houses. “I was once in a dark place,” Zay says, thinking back to his time as a depressed gay boy living in Virginia. He says he never would have dreamed of a fulfilling career as a dancer, performing in music videos for Sam Smith and on hit shows such as Ryan Murphy’s Golden Globe–nominated series Pose. “Ballroom kind of saved my life,” he says.

https://www.theatlantic.com/photo/2019/11/nyc-kiki-community/599830/